Ikh Turgen Uul

August 9-11, 2024

4029m

Nogoonnuur, Mongolia

“Turgen” is a rather common name but this one is the “ultra prominent peak” that locates on the far NW corner of Mongolia within a few kilometers from Russian border. There was absolutely no “beta” on the internet and even so, Gangaa, the so-called “most famous mountaineer in Mongolia” as well as the head guide of our company was not aware of any ascent of this objective. It eventually turned out that the locals living in the valley recalled that a team of five Mongolians climbed it in 1994, and another Russian team-of-7 summitted in 2004 and left a note in a register but that’s probably it. Those accounts were not accessible online so we essentially planned it as if we were doing a first ascent. The only source of information was the satellite images and we anticipated at least 700 vertical meters of glacier travel with unforeseen difficulties, so Gangaa decided to offer us a second guide. Naraa had recently soloed Khan Tengri and our original guide, Manlai had also climbed Khan Tengri as well as Shishapangma so Petter and I definitely had a strong team here. The viable approach from the east side seemed long and the drivable end was unknown, so we planned to tackle it over 3 days and Gangaa helped arranging two camels to carry our loads to the base camp in the valley. There is a road that goes closer from the north but there’d have more unknowns. Petter and I talked about it but eventually decided to go with the one with a bit more contingency despite the longer distance.

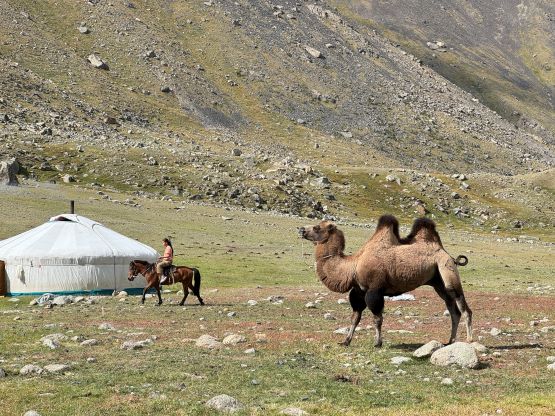

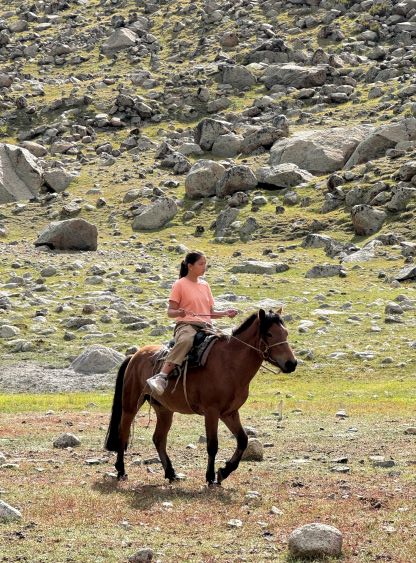

In the previous day we made a long and rough drive to Nogoonnuur and camped on the flats outside the town. We grouped with Naraa as well as the additional (local) support members on the following morning and drove together to near the drivable end 2350 m elevation. This was quite a bit higher than I thought based on the limited information from the satellite images but that’s great. The team did the job well as the road was definitely pushing the limit for the Landcruisers, especially for the one without the low range. Petter and I wondered about the camels but they showed up later in the afternoon out of nowhere together with two horses, concluding our entire support team – one cook, one driver, two Landcruisers, two guides, two camels, two horses and two local supporters. Things were getting fancy for a mere 3-day expedition and not to mention that Petter and I each had an individual 3-person tent. The camels were capable carrying 200 kg of load (each) so we would ferry all tents, cooking gears and loads of climbing equipment up the valley. Of course the climb turned out to be mostly non-technical and I didn’t even use the rope after all.

The plan for the first day was simply trekking to the base of Turgen, ideally as far up the valley as possible to set up the base camp, but the camp location was restricted to the camels’ abilities. Those camels could not walk on extensively rocky terrain and must need grass to feed, so we couldn’t go all the way to the edge of the glacier but that’s okay. We estimated the trekking distance to be around 15 km so there’s no need to start too early. We woke up naturally and did the morning routine rather lazily. Our local guides (on horseback) did a good job leading us traversing into their valley without losing much elevation, and we stopped at the first yurt for some welcoming Mongolian food. The continuation of the trekking involved a few creek crossings but those were all doable by rock-hopping. We had some unofficial trails to follow for most of it but did encounter at least one large swampy section. We stayed higher on the way out two days later and found a better way around. Eventually we settled at the outflow of a lake which was basically the end of camel territory. It wasn’t as far as I was hoping for but would make do. It rained on and off in the afternoon and part of me was glad that we got the tents set up rather quickly. It seemed like we had entered a period of unstable weather unfortunately, but the weather forecasts (from U.S. and Europe) were not reliable at all for this area. Petter went out for a 2-hour scouting mission once the rain stopped and I also walked a short ways up the valley to as far as the shore of the next lake, mostly to kill time. Meanwhile there were car-sized boulders tumbling down from the south side of the valley, high up on the glacial faces. Our camp was not in immediate danger, thankfully.

We had some disagreements about the starting time. I wanted to start much earlier than sunrise due to the unknown technical difficulties and the unstable afternoon weather, but everyone else preferred to have breakfast at 5 AM and start hiking shortly before sunrise. We still had about 2 hours worth of tedious terrain to cover before even reaching the glacier, mostly boulder hopping with only occasional walking on grass and scree. Naraa and I went ahead and waited on the edge of the glacier for at least half an hour for Petter and Manlai to catch up. The glacier was as expected, all ice with absolutely no snow so I refused to be roped up there, whereas the three of them decided to form a rope team. I then went up on my own and essentially did the rest of the climb solo as I would be much faster especially while not having to deal with the ropes. There was about 600 m elevation gain to the west peak on mostly 30-degree glacial ice, and that was easy enough for me to just crampon my way up. I encountered numerous sizeable crevasses about 2/3 of the way up, but the navigation was fairly easy without any sketchy crossing. The slope above those crevasses to the west peak was very foreshortened and took me a while.

I actually went all the way to the very top of this west peak (which has at least 30 m prominence), only to discover a shear drop on the opposite side. But before searching for a way down into the saddle I took my time studying the route for the final summit push. My fear was that we might have to detour climber’s left onto some steep glacial ice (which needed to be protected), but that was thankfully not the case. The direct ridgeline appeared to be mostly 3rd class rock and my plan was to find a non-technical route on rock hence completely independent from the rest of the team. I had no idea when or whether they would show up so it’s better to get the ball rolling while I had the oppourtunity to make my own decisions. After formulating a plan I had to focus on the immediate problem ahead, that was to find a non-technical way down into the saddle. I removed the crampons and scrambled north along the ridge and found a steep chute that appeared “doable” except for the initial ice finger. Down-climbing the ice using two tools would be feasible but I tried hard to scramble down on skier’s right, encountering some 4th class moves. I eventually was forced to make a gear transition and down-climbed the bottom half of that ice finger which necessitated several proper ice and mixed climbing moves, and kept the crampons for the rest of the class 2 descent to the saddle.

For the bottom half of the final summit push I stayed on the climber’s left on 35-degree ice and then hopped onto the rock ridge just as I planned. I traversed climber’s right on some exposed ledges after bashing my way up a steep but loose chute, and that put me in the next gully system farther climber’s right, which appeared to be at most 3rd class. The plan worked out well, but I encountered one crux step with a patch of ice complicating things up. I was too lazy to do two more gear transitions but the moves I did to overcome that ice patch were definitely not trivial. I did eventually had to put the crampons back on as I made my way onto the summit ridge, which was essentially an ice arete. The climbing was straightforward but the exposure as getting real. I did also have to remove the crampons for the last 50 horizontal meters to the true summit, which required a few more 3rd class moves on ledges. At this point I could see the others topping out on the west peak but they weren’t seem to be moving any farther. In any case I tagged the true summit and found a rusty and wet register left by a Russian party 20 years ago. I couldn’t understand anything but I could make out the date and the email address that they had left.

I made a hasty descent following the exact same route that I took, including that crux step which I opted for a uncontrolled but planned glissade. The ice patch was only several meters long and it’s much easier to sit on the butt and slide than to put the crampons back on. I could finally see two of them descending much farther skier’s left (not the ice finger that I used) down into the col, and we got back to the saddle at the exact same time. Petter informed me that the guides didn’t want to continue for reasons that the rock scrambling was “too difficult”, which didn’t make much sense to me. I offered Petter to guide him through the rock bands but I also had to make a decision for myself. The guides reluctantly followed, so I turned around after regaining 100 m elevation due to the incoming weather system. The clouds were getting darker and for me that’s a sign to leave. I dashed back down to the col, and climbed the full length of that ice finger (mostly for fun) and that’s when I got hailed on. I then mostly “ran” down the 600 m glacier descent racing with the weather, and did manage to beat the thunderstorms. A few minutes before reaching my ditched trail-runners it started to rain rather heavily, and another 10 minutes later there came the loud sounds of thunders. I was worrying about the rest of the team up on the summit but the only thing I could do was to dash back to camp as quickly as possible. I didn’t bother to change footwear but donned rain jacket and pack cover. The scrambling back across those wet boulder fields with loud thunders above was nowhere “fun”, but at least not difficult. I stumbled back to camp at around 2:30 pm, Nara showed up at around 5 pm and Petter and Manlai showed up another hour later. I witnessed two additional rock slides on the south side of the valley and one of them came quite close to our camp. I would listen and stay alert throughout the night and never fully zipped up the tent so I could run, if needed.

On the third day we woke up at around 8 am under bluebird skies, but we could see pieces of clouds approaching from the west. I feared that it would start to rain again at noon, so we’d better get going. The camels returned as promised, so we loaded them up in about an hour. There wasn’t much worth noting about the return hike except for the river crossings were slightly more difficult than two days earlier, likely due to the copious amount of precipitation. We stopped at that same yurt for lunch, and finished the rest of the return rather leisurely. The rain never came (which was good), and we decided to spend another night at the car-camp. There was spotty reception on some specific locations and the mosquitoes situation was actually tolerable, so why not. The plan for the following day was to make a long drive southwards to the city of Khovd to finally have a hotel stay. We would also meet up with the famous Gangaa in Khovd but on the next day. En route we stopped in Ölgii for lunch and the serving portion was surprisingly enormous. I was not impressed by the hotel in Khovd though. This was our first chance of taking a shower since Norway and the shower barely worked, and there’s no air conditioning whatsoever, and furthermore Petter and I had to share a room even though Adam was not refunded for this part of the trip. Had Adam been here with us would that mean he had to sleep on the floor? The food in this country is decent but the cell services and shower situation are much worse than some of the African countries I’ve visited, but whatever. I got a shower and that’s better than nothing.